But just not the same Hollywood Studios you may have been thinking of.

Nearly seven decades ago, Walt Disney and his talented staff of animators created a place called Hollywood Studios that served as the setting for the 1939 Donald Duck cartoon,

The Autograph Hound. I have frequently noted that many of Disney’s animated shorts are windows to the popular culture of bygone days, and

The Autograph Hound is very distinctly a snapshot in time of Hollywood during its golden era.

The hallmarks of this Donald Duck vignette are the numerous celebrity-inspired characters that were created to populate the fictional movie studio that Donald gate-crashes in search of autographs.

The first “celebrity” that Donald encounters within the walls of Hollywood Studios is the then well known character actor Henry Armetta. Famous for his ethnic-Italian personas, he was an almost constant presence in films during the era, appearing in thirteen films over the course of 1938-1939 alone. Next Donald encounters a mischievous Mickey Rooney who, unlike Armetta, achieved enormous fame and still enjoys a film career, now some seventy years later.

The cartoon’s only other surviving caricature is Shirley Temple. A precocious child actress, Temple was one of the brightest stars in Hollywood when

The Autograph Hound was produced and released. In the 1935 movie

The Little Colonel, her dancing skills were showcased when she and costar Bill “Bojangles” Robinson famously tap dance up and down a staircase. Temple is similarly dancing on stairs when Donald collides with her in

The Autograph Hound.

While Shirley Temple’s fame extended far, far beyond the end of her film career, the Ritz Brothers and Sonja Henie have somewhat faded into Hollywood obscurity and are little remembered now in the 21st century. Like Temple, they were featured prominently in the short, sharing extended interactions with Donald Duck.

Al, Jimmy and Harry Ritz were a trio of brothers famous for their synchronized dancing, slapstick comedy and celebrity impersonations. They made the leap from stage and vaudeville productions to movies in the mid-1930s. They were reaching the peak of their fame at the time

Autograph Hound was in production. 20th Century Fox headlined them in a number of films, starting with

Life Begins in College in 1937.

Henie catapulted to fame in the late 1920s when she took the figure skating sport by storm. From her Wikipedia entry:

Henie won the first of an unprecedented ten World Figure Skating Championships in 1927 at the age of fifteen, and her first Olympic gold medal the following year. She also won six consecutive European championships. She is credited with being the first figure skater to adopt the short skirt costume in figure skating, and make use of dance choreography. Her innovative skating techniques and glamorous demeanor transformed the sport permanently and confirmed its acceptance as a legitimate sport in the Winter Olympics.

Henie signed with Fox in 1936 and starred in a string of successful films through the mid-1940s.

The Autograph Hound was actually the second time that Henie was paid homage to in a Disney Cartoon. Released earlier in 1939,

The Hockey Champ features an ice skating Donald Duck doing a brief impersonation of the star, complete with her trademark curly hair and long, dark eyelashes.

While these stars were featured in extended sequences with Donald, the bulk of the cartoon’s celebrity cameos are found in a fast paced montage near the end of the film. In a little more than thirty seconds, there is a total of twenty star caricatures that flash across the screen:

Screen legends Greta Garbo and Clark Gable share a passionate embrace, despite their well known and often public statements that expressed a very clear and mutual animosity.

Mischa Auer, Joan Crawford, Groucho Marx and brother Harpo, and ventriloquist dummy Charlie McCarthy, although his right hand man Edger Bergen is noticeably absent. The pair would eventually appear in Disney's feature film

Fun and Fancy Free.

Eddie Cantor, Katherine Hepburn, Slim Summerville, Irvin S. Cobb and Edward Arnold.

Hugh Herbert, Roland Young, the long-censored Stepin Fetchit, and big mouths Joe E. Brown and Martha Raye.

Three appearances are notable in the fact that the personalities are featured in roles they were famous for when the cartoon was released in 1939. Bette Davis is garbed as her character from the 1938 film

Jezebel, for which she was awarded a Best Actress Oscar. Lionel Barrymore appears as his character of Dr. Gillespie from the series of

Dr. Kildare movies that were then just getting underway. Lastly, Charles Boyer is in his role of Napoleon Bonaparte from the 1937 film

Conquest.

One final odd and interesting detail from the cartoon--when Donald collides with a painted backdrop that ultimately bounces him toward his collision with Shirley Temple, the set is identified with a sign that reads

The Road to Mandalay. This was at one time the working title of what would become the first of the famous "Road" pictures that starred Bing Crosby, Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour. Originally offered to George Burns and Gracie Allen, and then to Fred MacMurray and Jack Oakie, it eventually evolved into

The Road to Singapore and arrived in theaters in March of 1940, some six months after

The Autograph Hound premiered.

Images © Walt Disney Company

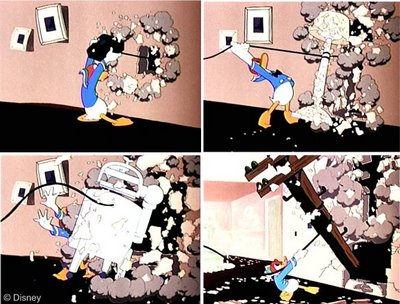

The highlight of Cured Duck is a Donald Duck temper tantrum of epic proportions. After being frustrated by an obviously latched window, he goes on a destructive rampage, of which Daisy’s house is the primary victim. It’s an incredibly rapid sequence of events. Witness when Don rips a telephone from a wall, and then subsequently drags a lamp and washing machine through the plaster as well, followed finally by the phone pole itself:

The highlight of Cured Duck is a Donald Duck temper tantrum of epic proportions. After being frustrated by an obviously latched window, he goes on a destructive rampage, of which Daisy’s house is the primary victim. It’s an incredibly rapid sequence of events. Witness when Don rips a telephone from a wall, and then subsequently drags a lamp and washing machine through the plaster as well, followed finally by the phone pole itself: An interesting bit of 1940s pop culture: when Donald symbolically transforms into a heel after his initial tirade, it bears the Wingfoot brand name.

An interesting bit of 1940s pop culture: when Donald symbolically transforms into a heel after his initial tirade, it bears the Wingfoot brand name.