It’s been a dozen years since the happy anomaly that is Runaway Brain debuted in theaters alongside the now forgotten feature film A Kid in King Arthur’s Court. This cartoon emerged over forty years after the studio produced its last traditional format Mickey Mouse cartoon short, The Simple Things, in 1953. It is a dynamic, hip and fun seven minutes of animation, very much awash in 1990s popular culture, yet still thankfully grounded in the creative sensibilities of the Hyperion Avenue era of Disney production.

It’s been a dozen years since the happy anomaly that is Runaway Brain debuted in theaters alongside the now forgotten feature film A Kid in King Arthur’s Court. This cartoon emerged over forty years after the studio produced its last traditional format Mickey Mouse cartoon short, The Simple Things, in 1953. It is a dynamic, hip and fun seven minutes of animation, very much awash in 1990s popular culture, yet still thankfully grounded in the creative sensibilities of the Hyperion Avenue era of Disney production.While Disney did not completely abandon Mickey Mouse cartoons during the decades following The Simple Things, the two efforts that preceded Runaway Brain, Mickey’s Christmas Carol and The Prince and the Pauper, were longer form literary adaptations and somewhat removed from the more traditional cartoon short format. Runaway Brain returned Mickey to the classic time and pace of a one reel short subject, the very type of animated entertainment he pioneered some sixty years earlier.

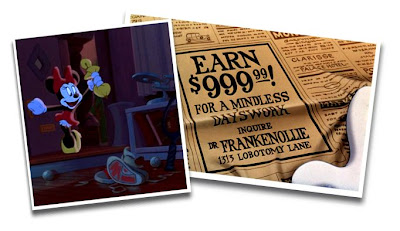

From its opening frames however, there is no mistaking Runaway Brain’s modern age pedigree. After its King Kong-esque opening title is quickly clawed into tatters, the audience is met with a joystick-wielding Mickey totally immersed in a Mortal Kombat style video game based on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Minnie arrives for an anniversary date and is quickly put off by Mickey’s inattention. Mickey tries to make a amends but digs himself even deeper when Minnie mixes up newspaper ads and misinterprets 18 holes of mini golf for an 18-day Hawaiian cruise.

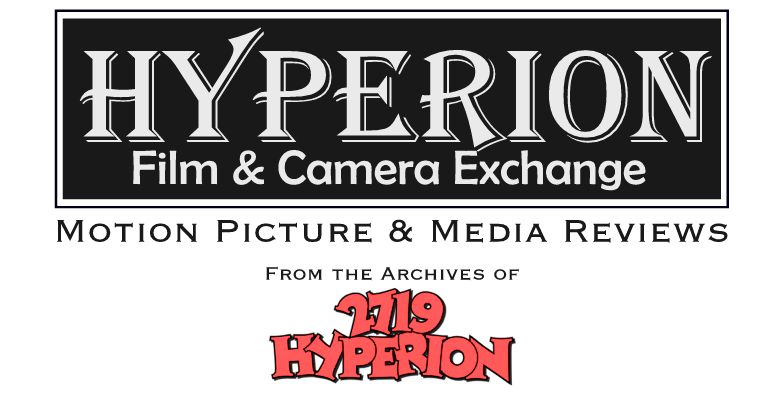

Desperately in need of a $1000 windfall, Mickey follows a want ad to the laboratory of simian mad scientist Dr. Frankenollie, whose devious plan is to do a brain swap between the mouse and his monstrous lab assistant Julius. Frankenollie features, albeit briefly, the voice talents of Kelsey Grammer, while Julius is in fact portrayed by Disney career villian Pete, whose peg leg was returned after a fairly extended PC-related sabbatical. Brains are switched, the good doctor is incinerated, and the short plunges into a frantic paced tour de force of action and heroics with a rough and tumble cityscape atmosphere more akin to recent Spiderman flicks than to traditional Mickey Mouse adventures.

Desperately in need of a $1000 windfall, Mickey follows a want ad to the laboratory of simian mad scientist Dr. Frankenollie, whose devious plan is to do a brain swap between the mouse and his monstrous lab assistant Julius. Frankenollie features, albeit briefly, the voice talents of Kelsey Grammer, while Julius is in fact portrayed by Disney career villian Pete, whose peg leg was returned after a fairly extended PC-related sabbatical. Brains are switched, the good doctor is incinerated, and the short plunges into a frantic paced tour de force of action and heroics with a rough and tumble cityscape atmosphere more akin to recent Spiderman flicks than to traditional Mickey Mouse adventures. But Runaway Brain is not as disconnected from Mickey’s cartoon heritage as one might think. Scratch below it’s video game, surf shop and other contemporary trappings and you have a short produced from very much the same disciplines behind Disney’s earlier short subject cartoons. The brain exchange that takes place between Mickey and Julius is an especially notable achievement in character animation and a credit to Andreas Dejas and his team; it effectively transplants Mickey’s personality into the monstrous Julius, and likewise turns a long standing corporate icon into a raving psychopath. In addition, director Chris Bailey was not afraid to move his non-existent camera around and approach shots from wholly unorthodox angles, as demonstrated by the sequence where a Julius-possessed Mickey scampers up through the laboratory’s pipes and conduits to dramatically emerge before the city skyline. Early Disney animators used similar “camera moving” techniques as far back as the early 1930s.

But Runaway Brain is not as disconnected from Mickey’s cartoon heritage as one might think. Scratch below it’s video game, surf shop and other contemporary trappings and you have a short produced from very much the same disciplines behind Disney’s earlier short subject cartoons. The brain exchange that takes place between Mickey and Julius is an especially notable achievement in character animation and a credit to Andreas Dejas and his team; it effectively transplants Mickey’s personality into the monstrous Julius, and likewise turns a long standing corporate icon into a raving psychopath. In addition, director Chris Bailey was not afraid to move his non-existent camera around and approach shots from wholly unorthodox angles, as demonstrated by the sequence where a Julius-possessed Mickey scampers up through the laboratory’s pipes and conduits to dramatically emerge before the city skyline. Early Disney animators used similar “camera moving” techniques as far back as the early 1930s. More than anything, Runaway Brain is a successful creative marriage of the Mouse’s very early and certainly less inhibited black and white efforts with the later Technicolor productions that featured a much more benign Mickey but were rich in style and layered upon lush, detailed backgrounds.

More than anything, Runaway Brain is a successful creative marriage of the Mouse’s very early and certainly less inhibited black and white efforts with the later Technicolor productions that featured a much more benign Mickey but were rich in style and layered upon lush, detailed backgrounds. While the occasional pundit has made note of this uncharacteristic approach to Mickey and has even speculated that that is why it has been largely unseen in the years since its release, its darker and wilder dynamic is not unprecedented. Mickey explored similar avenues in early cartoons such as The Haunted House, The Gorilla Mystery and The Mad Doctor, just to name a few. Dr. Frankenollie’s lab is an obvious throwback to Universal’s classic monster films, but no doubt also received some inspiration from Mickey’s similarly styled 1937 cartoon The Worm Turns.

While the occasional pundit has made note of this uncharacteristic approach to Mickey and has even speculated that that is why it has been largely unseen in the years since its release, its darker and wilder dynamic is not unprecedented. Mickey explored similar avenues in early cartoons such as The Haunted House, The Gorilla Mystery and The Mad Doctor, just to name a few. Dr. Frankenollie’s lab is an obvious throwback to Universal’s classic monster films, but no doubt also received some inspiration from Mickey’s similarly styled 1937 cartoon The Worm Turns.Runaway Brain’s unconventional nature was also likely influenced by the trio of Roger Rabbit cartoons that preceded it during the early 1990s. That is especially evidenced by the number of inside jokes its creators slipped into the film. While references to The Exorcist, veteran Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, and even a regurgitated Zazu are relatively obvious, it takes a keener eye to spot the newspaper homage to Clarisse, the torch-singing counterpart to Chip and Dale in the 1951 short Two Chips and a Miss. The monster’s name Julius is a possible reference to one of Pete’s earliest of co-stars, a cat character from the pre-Mickey series of Alice comedies. And it appears that Mickey must be a Trekkie of sorts, as a model of the Starship Enterprise can be seen in a corner of his living room.

Preschooler moms beware--this is not your standard toddler-friendly Mickey Mouse cartoon. Hence its inclusion on a Disney Treasures DVD rather than in the more inclusive Cartoon Classics line. Modern audiences may be jarred somewhat by its darker, irreverent tone, but most animation buffs would likely view Runaway Brain as a return to Mickey’s earlier, often times impudent, sometimes scary, and definitely more uninhibited, black and white years.

Preschooler moms beware--this is not your standard toddler-friendly Mickey Mouse cartoon. Hence its inclusion on a Disney Treasures DVD rather than in the more inclusive Cartoon Classics line. Modern audiences may be jarred somewhat by its darker, irreverent tone, but most animation buffs would likely view Runaway Brain as a return to Mickey’s earlier, often times impudent, sometimes scary, and definitely more uninhibited, black and white years.Images © Walt Disney Company

0 comments:

Post a Comment